Hyperlight Wasm: Fast, secure, and OS-free

March 26, 2025 · 10 min read

By Yosh Wuyts, Senior Developer Advocate and Lucy Menon, Software engineer and researcher, Microsoft

Last fall the Azure Core Upstream team introduced Hyperlight : an open-source Rust library you can use to execute small, embedded functions using hypervisor-based protection. Then, we showed how to run Rust functions really, really fast , followed by using C to run Javascript . In February 2025, the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) voted to onboard Hyperlight into their Sandbox program.

We're announcing the release of Hyperlight Wasm: a Hyperlight virtual machine (VM) "micro-guest" that can run wasm component workloads written in many programming languages. If you'd like to dive straight in, you can visit the hyperlight-wasm repo on GitHub. In the remainder of this post we'll cover the basics of how Hyperlight Wasm works and then walk through how to build a Rust example step-by-step.

Performance and compatibility

Traditional virtual machines do a lot of work to be able to run programs. Not only do they have to load an entire operating system, they also boot up the virtual devices that the operating system depends on. Hyperlight is fast because it doesn't do that work; all it exposes to its VM guests is a linear slice of memory and a CPU. No virtual devices. No operating system.

But this speed comes at the cost of compatibility. Chances are that your current production application expects a Linux operating system running on the x86-64 architecture (hardware), not a bare linear slice of memory. And compatibility is not just limited to operating systems; it can be discussed at three distinct levels:

Operating system: Linux, macOS, and Windows provide a portable abstraction across different hardware.

System interface layer: System interface standards such as Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX) and the WebAssembly System Interface (WASI) provide interoperability across operating systems.

Programming language/library: Programming languages' standard libraries and runtimes provide interoperability across system interfaces.

Targeting compatibility with an OS at that layer allows one to abstract over the language/runtime that a customer might want to use, because common OS's are almost universally supported by languages, libraries, and application programs—but that comes at the cost of requiring that a specific relatively-heavyweight execution environment be provided. On the other hand, very lightweight services can and do abstract over the details of their not-a-full-OS execution environment by changing the standard library of a single language to support their platform, which offers vastly improved performance—at the cost of requiring that a specific language be used to implement programs running in that environment.

WASI and the WebAssembly Component Model provide a middle ground between these contrasting abstractions: by implementing these interfaces, one can allow any lightweight execution environment to run programs written in (nearly) any language. Hyperlight Wasm takes advantage of this to allow you to implement a small set of high-level, performant, abstractions in almost any execution environment and provide a very fast, hardware protected, but nevertheless widely-compatible execution environment.

Introducing the Hyperlight Wasm guest

How compatible? Well, building Hyperlight with a WebAssembly runtime— wasmtime —enables any programming language to execute in a protected Hyperlight micro-VM without any prior knowledge of Hyperlight at all. As far as program authors are concerned, they're just compiling for the wasm32-wasip2 target. This means they can run their programs locally using runtimes like wasmtime or Jco . Or run them on a server using for Nginx Unit , Spin , WasmCloud —or now also Hyperlight Wasm . If done right, developers don't need to think about what runtime their code will run on as they're developing it. That is a degree of developer flexibility that is only possible through standards.

Executing workloads in the Hyperlight Wasm guest isn't just possible for compiled languages like C, Go, and Rust, but also for interpreted languages like Python, JavaScript, and C#. The trick here, much like with containers, is to also include a language runtime as part of the image. For example, for JavaScript, the StarlingMonkey JS Runtime was designed to natively run in WebAssembly.

Programming languages, runtimes, application platforms, and cloud providers are all starting to offer rich experiences for WebAssembly out of the box. If we do things right, you will never need to think about whether your application is running inside of a Hyperlight Micro-VM in Azure. You may never know your workload is executing in a Hyperlight Micro VM. And that's a good thing.

More layers of security, fewer layers in total

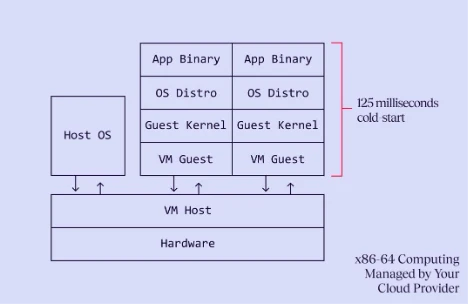

The big magic trick we're performing by combining Hyperlight with WebAssembly is that we're achieving more security and performance than traditional VMs by doing less work overall. When traditional virtual machine managers (VMMs) create a new virtual machine, they first need to create new virtual devices, then load a kernel, then load an operating system, and only then are they able to start the application. The lower end of this will take about 125 milliseconds.

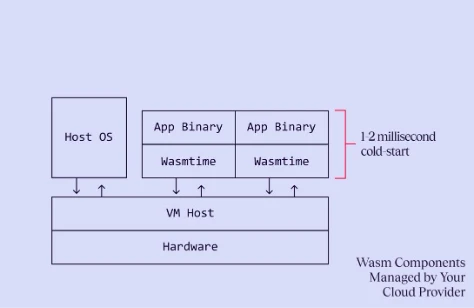

With Hyperlight and Hyperlight Wasm we end up doing far less than traditional VMs. When the Hyperlight VMM creates a new VM, all it needs do to is create a new slice of memory and load the VM guest, which in turn loads the wasm workload. This takes about 1-2 milliseconds today, and work is happening to bring that number to be less than 1 millisecond in the future.

Not only is this architecture good for start times, fast start times also affect the way you can schedule your applications. If starting a workload takes about a millisecond, you can afford not to have any idling instances. If you do choose to have a warm pool ready, the memory footprint is drastically smaller. It also allows you to do more work on cheaper hardware, located closer to users. That's the logic behind our upcoming Azure Front DoorEdge Actions service, powered by Hyperlight and soon to be in private preview.

Combining Hyperlight with wasm is not just good for performance either; it is also good for security. Under the covers, the Hyperlight Wasm guest uses the best-in-class Wasmtime runtime, compiled into a Hyperlight guest as a Rust no_std module. Wasmtime provides strong isolation boundaries for wasm workloads via a software-defined runtime sandbox. While potential attackers will have a bad time breaking out of wasm's sandbox, on the Hyperlight Wasm guest, even if they could manage to, they would be facing the challenge of then also escaping the VM. One layer of sandboxing is good. But having two layers is even better.

UDP echo example

Alright, let's look at how to use Hyperlight Wasm from Rust. For our example, we'll run a simple User Datagram Protocol (UDP) echo server that uses a portion of the wasi:sockets] interface. Luckily for us, we don't have to write that program ourselves: we can download a pre-compiled wasm program (if you want to compile it yourself, the source is available here ) and run it. Let's start by doing that first. Assuming you have a working Rust installation, start by installing the wkg tool to download wasm binaries from GitHub Artifacts, and then use that to get a copy of the wasm binary:

cargo install wkg

wkg oci pull ghcr.io/hyperlight-dev/wasm-udp-echo-sample/udp-echo-server:latest -o echo.wasmNow that we have a Wasm Binary, we can start wiring up the Hyperlight host. Right now that is a little complicated, since we haven't yet published cargo crates. So let's start by git cloning our example repo:

git clone https://github.com/hyperlight-dev/hyperlight-wasm-sockets-example

mv echo.wasm hyperlight-wasm-sockets-example

cd hyperlight-wasm-sockets-exampleIf you look at the code in the repo, you'll notice it is structured like a regular Rust project. That's because it is. It includes several files, most of which are there to implement boilerplate interfaces that the echo sample uses. In the root of the project there is a file called hyperlight.wit. This file is a text representation in the WebAssembly Interface Types (WIT) language that specifies the precise interfaces that the host is making available to, and expects to get from, the wasm module. We need to process this file into a binary wasm representation, which will be used when hyperlight-wasm is built:

wasm-tools component wit hyperlight.wit -w -o hyperlight-world.wasm

export HYPERLIGHT_WASM_WORLD=$(readlink -f hyperlight-world.wasm)Now, let's take a look at the code that uses hyperlight-wasm to run a component. To get bindings that we can use to easily implement imports/call exports of the wasm module, we can use hyperlight_component_macro::host_bindgen:

// bindings.rs

extern crate alloc;

hyperlight_component_macro::host_bindgen!();This generates a set of traits representing the WebAssembly component model instances imported and exported by the component inside the sandbox. We define a state structure which keeps track of everything we need to implement the imports (but in this sample application, that is not used):

// state.rs

pub struct MyState {}

impl MyState {

pub fn new() -> Self { MyState {} }

}We then need to specify that this state representation can be used to implement the interfaces that the component uses:

// main.rs

use bindings::*;

impl root::component::RootImports for MyState {

type Udp = MyState;

fn udp(&mut self) -> &mut Self { self }

// ... one for each imported instance

}The wasi:sockets udp interface is very simple to implement, since it doesn't actually have any functions not associated with a resource:

// udp.rs

impl wasi::sockets::Udp<

ErrorCode,

IpSocketAddress,

(),

MyPollable>

for MyState {} But, since it does export a UdpSocket resource, we need to implement that resource, specifying the host type that underlies it and how to implement its methods on the host:

impl wasi::sockets::udp::UdpSocket<

wasi::sockets::network::ErrorCode,

MyDatagramStream,

wasi::sockets::network::IpSocketAddress,

(),

MyDatagramStream,

MyPollable

>

for MyState {

type T = MySocket;

fn start_bind(

&mut self,

self_: BorrowedResourceGuard<MySocket>,

_network: BorrowedResourceGuard<()>,

local_address: wasi::sockets::network::IpSocketAddress

) -> Result<(), wasi::sockets::network::ErrorCode> {

*(*self_).os.lock().unwrap() = Some(Arc::new(

std::net::UdpSocket::bind(local_address)

.map_err(|_| wasi::sockets::network::ErrorCode::Unknown)?));

Ok(())

}

fn stream(

&mut self,

self_: BorrowedResourceGuard<Self::T>,

_remote_address: Option<IpSocketAddress>

) -> Result<(MyDatagramStream, MyDatagramStream), ErrorCode> {

let sock = (*self_).os.lock().unwrap();

let sock = sock.as_ref().unwrap();

Ok((MyDatagramStream { socket: sock.clone() },

MyDatagramStream { socket: sock.clone() }))

}

fn finish_bind(

&mut self,

_self: BorrowedResourceGuard<Self::T>

) -> std::result::Result<(), ErrorCode> {

Ok(())

}

fn r#subscribe(

&mut self,

_self: BorrowedResourceGuard<Self::T>

) -> MyPollable {

MyPollable::AlwaysReady

}

}Now that we have that, we're ready to run Hyperlight and point it to our Wasm binary. And all that takes is a little bit of boilerplate. In the code below, we're first creating a new Hyperlight sandbox with enough memory to run a Wasm runtime. Then, we're registering the bindings we just wrote. And finally, we load our Wasm Component and run it.

fn main() {

let state = State::new();

// Setup the sandbox with enough resources to run a Wasm runtime

let mut sb: hyperlight_wasm::ProtoWasmSandbox =

hyperlight_wasm::SandboxBuilder::new()

.with_guest_input_buffer_size(5_000_000)

.with_guest_heap_size(10_000_000)

.with_guest_panic_context_buffer_size(10_000_000)

.with_guest_stack_size(10_000_000)

.with_guest_function_call_max_execution_time_millis(0)

.build()

.unwrap();

// Register the host functions

let rt = crate::bindings::register_host_functions(&mut sb, state);

// Load our Wasm Component and run it

let sb = sb.load_runtime().unwrap();

let sb = sb.load_module("echo.wasm").unwrap();

let mut wrapped = bindings::RootSandbox { sb, rt };

let run_inst = root::component::RootExports::run(&mut wrapped);

let _ = run_inst.run();

}Finally, before we can run the sample Wasm binary, we need to Ahead-Of-Time compile it into a format that wasmtime can load without having to generate code at runtime:

cargo install --git https://github.com/hyperlight-dev/hyperlight-wasm --branch hyperlight-component-macro hyperlight-wasm-aot

hyperlight-wasm-aot compile --component echo.wasm echo.bin And now we're ready to start the application and run it. You can do that by running cargo run in one terminal, which will start a server listening on port 8080:

cargo runAnd in another terminal, we can now send User Datagram Protocol (UDP) packets. You can do that using the netcat utility as follows (for Windows you can find a netcat alternative here ):

nc -u 127.0.0.1 8080Now you're free to type! Whatever you send to the server will be echoed back. And that's the basics of Hyperlight's Wasm guest.

What's next?

So far we've mostly talked about using WASI on Hyperlight for portability between operating systems and VMs. But it doesn't just stop there: because the WebAssembly instruction set and the Component Model abstract binary interface (ABI) are not tied to any one machine architecture, wasm applications are also portable between different instruction sets. You can soon expect Hyperlight Wasm to also work on Arm64 processors. Rebuilding your host will just work, without you ever needing to recompile the wasm applications running inside.

You may also have noticed that, while we can support WASI APIs in the guest, the VMM host doesn't provide its own default implementation of WASI interfaces, so you have to implement them yourselves. While many applications will appreciate that flexibility, including cloud vendors like Microsoft who are using Hyperlight to create products, it does mean that getting started and trying things out can take some time. For that reason, we're planning to extend Hyperlight-Wasm with default bindings for some WASI interfaces soon. That way, if you just want to sandbox an HTTP server or a service that listens on a socket, you don't need to do much else to get started.

Get involved with Hyperlight

Hyperlight has been donated by Microsoft to the CNCF's Sandbox program. Our goal is to raise the bar for fast, efficient, and secure cloud-native computing. The Hyperlight Wasm guest is our latest addition to the Hyperlight project, making it convenient to write programs that run on Hyperlight.

As an open-source project licensed under the Apache 2.0 license, Hyperlight underscores Microsoft's commitment to fostering innovation and collaboration within the tech community. We welcome developers, solution architects, and IT professionals to help build and enhance Hyperlight. To get started with Hyperlight, please visit the repo at Hyperlight and let us know what you think.

Visit the Hyperlight repository on Github.

About the authors

Yosh Wuyts Senior Developer Advocate

Yosh is a Cloud Native Advocate at Microsoft based in Copenhagen, Denmark. They're a member of the Rust Async WG and a Bytecode Alliance Recognized contributor. They're also a proud cat dad and enthusiast cook.

Lucy Menon Software engineer and researcher, Microsoft

Lucy Menon is a software engineer and researcher at Microsoft working on Hyperlight and formalizing the WebAssembly Component Model.